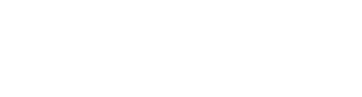

HUJUI KITU is a Swahili phrase meaning ‘you know nothing’ and is a good rubric to adopt in life, because if you know nothing you may begin to learn something, whereas if you think you know everything you will never learn anything. I first came across the phrase as the inscription on a printed cloth, kanga, which I bought in Darajani market on Zanzibar during my first visit to eastern Africa. It might be worn by an older woman, perhaps to comment on her younger rivals, and it gave me my first insight into this extraordinary textile tradition, about which I too ‘knew nothing’.

HUJUI KITU is a Swahili phrase meaning ‘you know nothing’ and is a good rubric to adopt in life, because if you know nothing you may begin to learn something, whereas if you think you know everything you will never learn anything. I first came across the phrase as the inscription on a printed cloth, kanga, which I bought in Darajani market on Zanzibar during my first visit to eastern Africa. It might be worn by an older woman, perhaps to comment on her younger rivals, and it gave me my first insight into this extraordinary textile tradition, about which I too ‘knew nothing’.

I was educated at Malvern, Brasenose College Oxford and Heatherley’s School of Art before becoming a curator of the African collections of the British Museum (BM) in 1987. My doctorate in Professional Studies by Public Works is from Middlesex University. The Sainsbury African Galleries opened to the public at the BM in 2001, and during my time as

a curator I concentrated in particular on making the displays more representative of the whole continent and of ‘global Africa’ as well as building up the Museum’s collections of textiles and of works by contemporary artists of African heritage.

I was educated at Malvern, Brasenose College Oxford and Heatherley’s School of Art before becoming a curator of the African collections of the British Museum (BM) in 1987. My doctorate in Professional Studies by Public Works is from Middlesex University. The Sainsbury African Galleries opened to the public at the BM in 2001, and during my time as

a curator I concentrated in particular on making the displays more representative of the whole continent and of ‘global Africa’ as well as building up the Museum’s collections of textiles and of works by contemporary artists of African heritage.

I have worked with artists in many African countries and around the world, while at the same time developing my own practice in London, first at the Small Mansion Arts Centre, Gunnersbury, then at Palace Wharf, Fulham and now at the West London Art Factory, Park Royal. I have helped to organise TRIANGLE artists’ workshops in Mozambique, Ghana and Nigeria, and recently co-curated with John Giblin the very well-received exhibition SOUTH AFRICA, The Art of a Nation at the BM which included the work of more than twenty South African contemporary artists.

I have worked with artists in many African countries and around the world, while at the same time developing my own practice in London, first at the Small Mansion Arts Centre, Gunnersbury, then at Palace Wharf, Fulham and now at the West London Art Factory, Park Royal. I have helped to organise TRIANGLE artists’ workshops in Mozambique, Ghana and Nigeria, and recently co-curated with John Giblin the very well-received exhibition SOUTH AFRICA, The Art of a Nation at the BM which included the work of more than twenty South African contemporary artists.

In 1996 the artist Magdalene Odundo introduced me to Meriel Hoare, a teacher whose approach to drawing has radically influenced my own practice. The following year I began the first of many fieldwork trips to African countries, during which I would invariably work with contemporary artists. In January 2001 the new African galleries at the British Museum opened with an emphasis on contemporary art – it was this event which helped to spark Gus Casely-Hayford’s idea of a festival of African art and culture which was to become Africa ’05. Gus became the Director of the National Museum of African Art in Washington D.C. and is now heading up the new V&A East Museum in London. In September of that year, by means of 150 paintings and drawings, I portrayed the human family which I had experienced and imagined in my life. Shortly after the opening of that one person exhibition, Green and Dying, I heard that the World Trade Centre in New York had been attacked.

In 1996 the artist Magdalene Odundo introduced me to Meriel Hoare, a teacher whose approach to drawing has radically influenced my own practice. The following year I began the first of many fieldwork trips to African countries, during which I would invariably work with contemporary artists. In January 2001 the new African galleries at the British Museum opened with an emphasis on contemporary art – it was this event which helped to spark Gus Casely-Hayford’s idea of a festival of African art and culture which was to become Africa ’05. Gus became the Director of the National Museum of African Art in Washington D.C. and is now heading up the new V&A East Museum in London. In September of that year, by means of 150 paintings and drawings, I portrayed the human family which I had experienced and imagined in my life. Shortly after the opening of that one person exhibition, Green and Dying, I heard that the World Trade Centre in New York had been attacked.

In 2002 I acquired for the BM two works by El Anatsui, Man’s Cloth and Woman’s Cloth which were the first two sculptures he made using the technique of sewing together flattened liquor bottle tops, a technique which would help to make him the world famous artist he is today. Later that year I purchased a sculpture for the British Museum by the Mozambican artist Kester. Constructed entirely of firearms, the Throne of Weapons – and the messages of peace and conflict resolution which it carried – struck a chord with audiences around the world and prompted me to commission a much larger sculpture from Bishop Sengulane’s Swords into Ploughshares project in Mozambique. That sculpture became known as The Tree of Life, and as it neared completion at the end of 2004 the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq had become the cornerstones of the global 'War on Terror'.

In 2002 I acquired for the BM two works by El Anatsui, Man’s Cloth and Woman’s Cloth which were the first two sculptures he made using the technique of sewing together flattened liquor bottle tops, a technique which would help to make him the world famous artist he is today. Later that year I purchased a sculpture for the British Museum by the Mozambican artist Kester. Constructed entirely of firearms, the Throne of Weapons – and the messages of peace and conflict resolution which it carried – struck a chord with audiences around the world and prompted me to commission a much larger sculpture from Bishop Sengulane’s Swords into Ploughshares project in Mozambique. That sculpture became known as The Tree of Life, and as it neared completion at the end of 2004 the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq had become the cornerstones of the global 'War on Terror'.

In February 2005 Africa ’05 opened, with The Tree of Life as one of its iconic images; that summer the 'July Bombings' hit London. Lives were lost and countless more changed forever, not least the huge numbers of innocent people who were suddenly viewed with suspicion and fear simply because of their appearance.

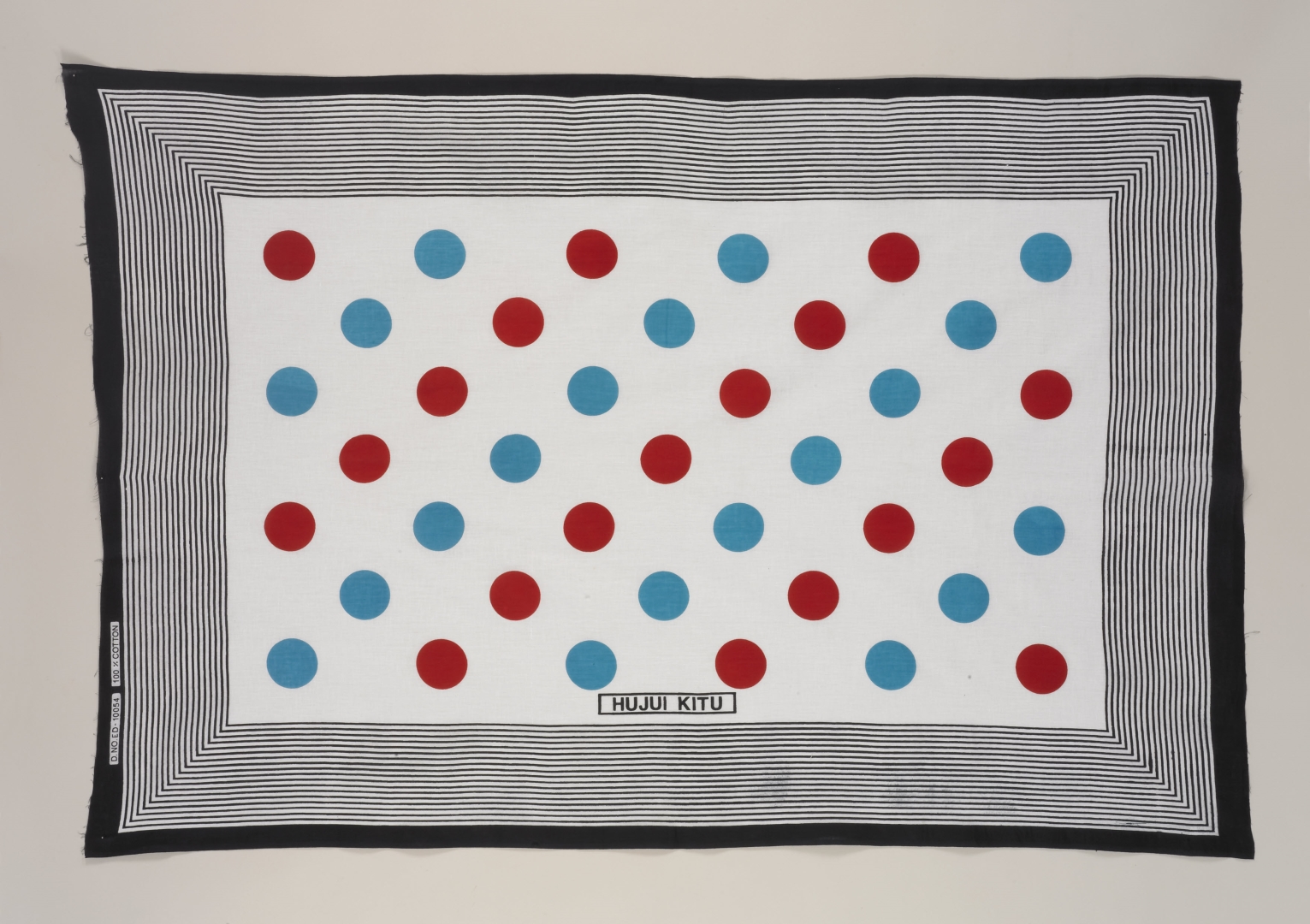

Since 2002 I had been working in eastern and southern Africa researching the global history, production and social significance of machine-printed and woven textiles. This became an ongoing research interest and developed into the exhibition Social Fabric at the British Museum which subsequently toured to four other venues around the UK.

Since 2002 I had been working in eastern and southern Africa researching the global history, production and social significance of machine-printed and woven textiles. This became an ongoing research interest and developed into the exhibition Social Fabric at the British Museum which subsequently toured to four other venues around the UK.

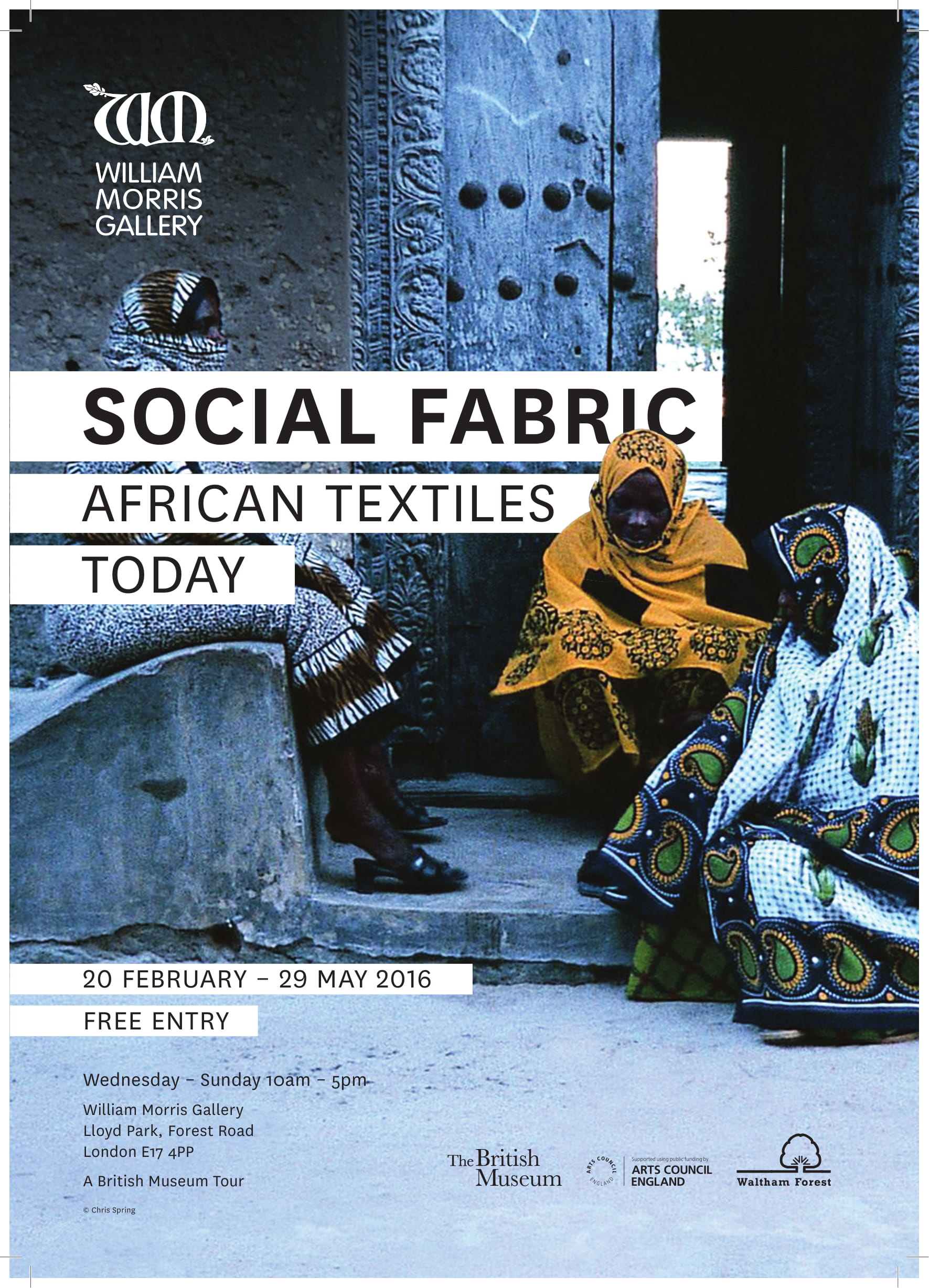

In 2006, while thinking how the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Atlantic Slave Trade might best be commemorated, I became aware for the first time not only of the details of the trade itself but of the breadth and depth of the psychological legacy it has left, and the bravery of those who struggled – and continue to struggle – against its almost unimaginable evil. The sculpture La Bouche du Roi by the Beninoise artist Romuald Hazoumé was purchased by and displayed at the BM in 2007 and subsequently toured the UK. It is a profound meditation on human greed and exploitation.

In 2006, while thinking how the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Atlantic Slave Trade might best be commemorated, I became aware for the first time not only of the details of the trade itself but of the breadth and depth of the psychological legacy it has left, and the bravery of those who struggled – and continue to struggle – against its almost unimaginable evil. The sculpture La Bouche du Roi by the Beninoise artist Romuald Hazoumé was purchased by and displayed at the BM in 2007 and subsequently toured the UK. It is a profound meditation on human greed and exploitation.

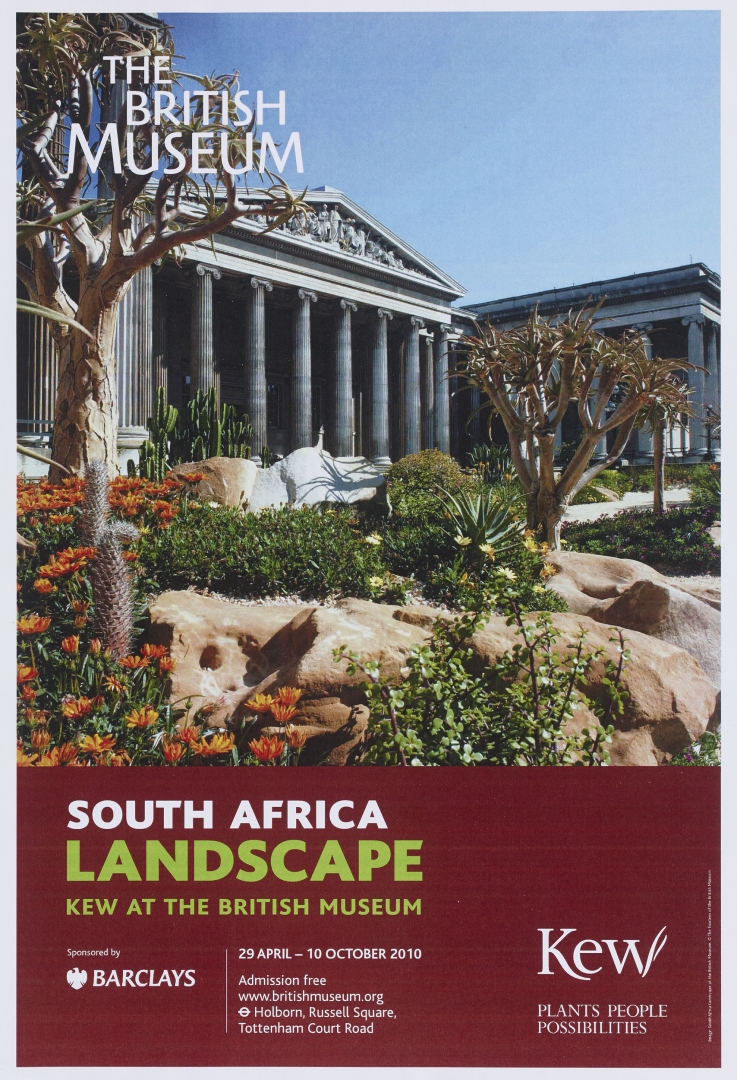

In 2010 I worked with June Bam-Hutchison on the South African Landscape exhibition at the BM. Her book, Peeping Through the Reeds, tells her own story of life under the apartheid regime in South Africa. It is a story of survival but also, in common with many of the other stories and events which have touched my life, it is a triumph of the human spirit.

In 2010 I worked with June Bam-Hutchison on the South African Landscape exhibition at the BM. Her book, Peeping Through the Reeds, tells her own story of life under the apartheid regime in South Africa. It is a story of survival but also, in common with many of the other stories and events which have touched my life, it is a triumph of the human spirit.

That triumph was reaffirmed for me in 2012, as I travelled through Japan towards Hiroshima with Kenji Yoshida, now Director General of the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, together with Bishop Sengulane of Mozambique - and again in 2013 as I went with the Algerian artist Rachid Koraïchi to the desert town of Temacine where the Tijani brotherhood was founded in the late eighteenth century.

That triumph was reaffirmed for me in 2012, as I travelled through Japan towards Hiroshima with Kenji Yoshida, now Director General of the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, together with Bishop Sengulane of Mozambique - and again in 2013 as I went with the Algerian artist Rachid Koraïchi to the desert town of Temacine where the Tijani brotherhood was founded in the late eighteenth century.

In 2015 I did fieldwork in South Africa researching the exhibition, South Africa – Art of a Nation, which I co-curated with John Giblin and which ran from 2016 to 2017, after which I moved on from the BM to develop my practice as an artist and writer at the West London Art Factory. I have been privileged to have met many remarkable people during these past years, people who have helped to shape my thoughts and my artistic practice, and I look forward to the coming years with great joy, though inevitably tempered by sadness at the memory of those dear friends and family who have passed on, including the late, great Robert Loder.